Always Being Born – Rediscovering Mrinal Sen at 100

It’s been more than three months since I last posted on my blog, blame it somewhat on my professional commitments and also a bit of can-always-do-it-tomorrow syndrome. All along, I thought of writing something on Mrinal Sen the auteur as this year is his birth centenary – but eventually gave up the idea as an opportunity lost.

His birthday, May 14, had come and gone. A few mainline vernacular magazines devoted their cover story to Sen, though what stood out was an extremely objective piece of remembrance by his son Kunal – a Chicago resident for ages. It was not surprising to see where Kunal got his DNA from as the master himself seemed averse to idolatry and ever ready to question.

This was just the beginning in terms of ‘celebration’ of his 100 years – at least three film projects are at varying stages of completion, including a personal film by Anjan Dutta, one of Sen’s protégés. An interesting, albeit low key, three-day festival is being planned at Alliance Francaise next month while the 29th edition of the Kolkata International Film Festival, scheduled in December, has announced their grandiose plans to pay tribute to Sen (alongwith Dev Anand). Hopefully, they will resurrect the interest level once again about this maverick filmmaker, who slipped away from public gaze ever since his last film Amar Bhuvan (My World) in 2002.

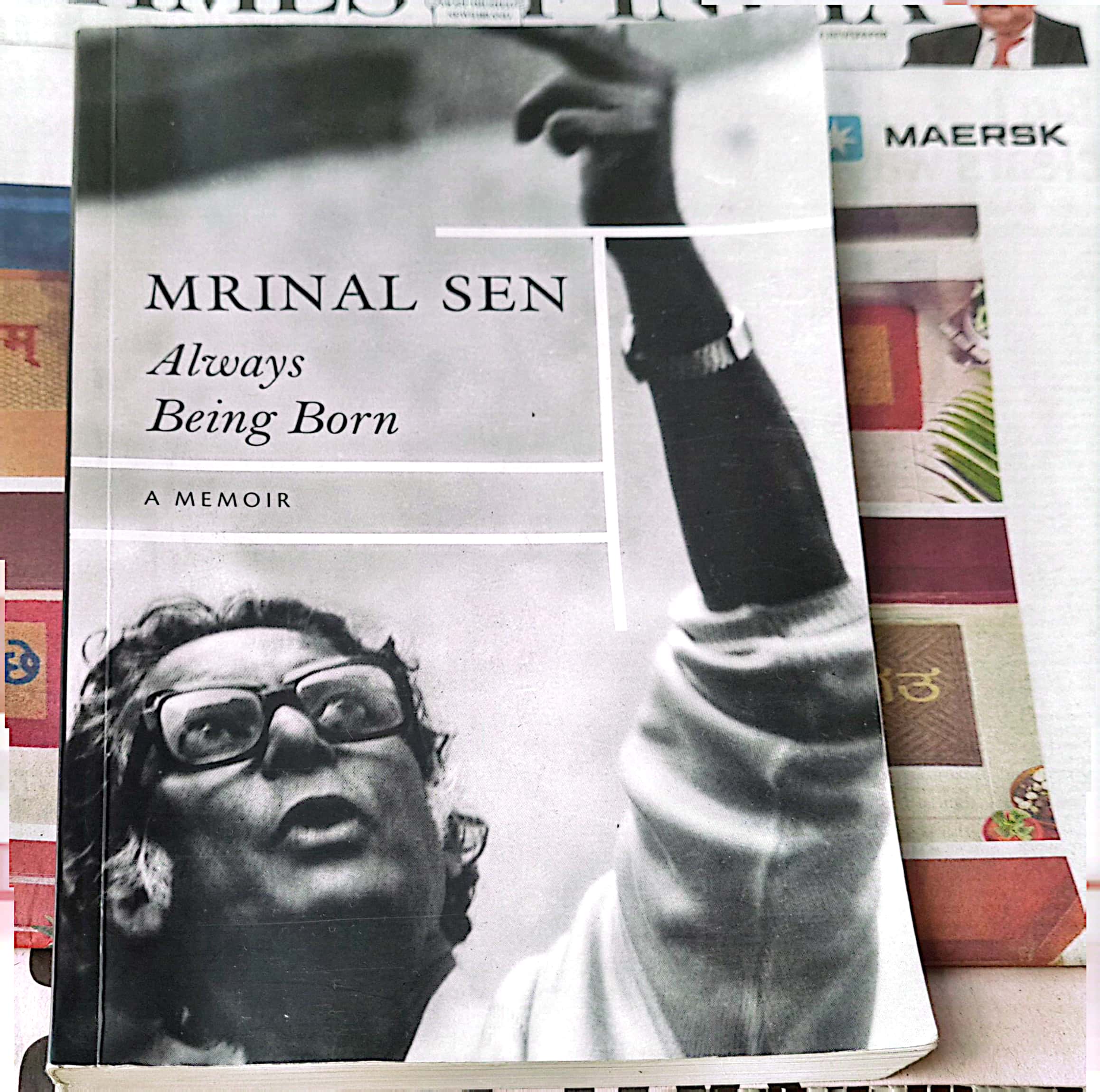

What, however, spurred me on was his memoir Mrinal Sen: Always Being Born which was republished by Seagull Publishers to coincide with his centenary. It was first published in 2004 (by Stellar Publishing) and turned out to be nothing short of a hidden gem for me – covering a huge canvas which spans through his childhood, partition, his politics and craft which was intertwined and of course his El Dorado – which he famously said about Kolkata.

‘’I am a filmmaker by accident and an author by compulsion,’’ he once said – though it was yet another example of him not taking himself seriously enough. It’s often said that be it literature, art or cinema, they reflect the times that we live in. The post-colonial Kolkata, where Sen grew up and thrived, was a different world altogether where his friends at regular adda session at a small café went on to become doyens in their respective fields – or there was this police sergeant on duty at a political rally who turned out to be a fan of Louis Malle, the French director.

A bit from the book sums up how the city, which once provoked him into producing some of his most seminal work like the trilogy of Interview, Calcutta 71 and Padatik still continued to fascinate him. ‘’Calcutta/Kolkata! Buoyant, creative, erratic, even hopelessly disengaged. For reasons of my own, having lived in my El Dorado for ages, I stop a while and look within and ask myself if I have at any point of time, felt sick of my city. Have I? Ever? Do I? Now? The truth is that I am so much a part of its anatomy.

‘’As I write this, I remember a Bob Dylan song – Love Sick (1997) – which not long ago, the actor-singer Anjan Dutt, my friend, made me listen to. I am sick of love/but I am in the thick of it. That was it – a kind of love-and-hate relationship with your lover, or mine. Inescapable. Maligned and loved, both in enormous proportions.’’

‘’As I write this, I remember a Bob Dylan song – Love Sick (1997) – which not long ago, the actor-singer Anjan Dutt, my friend, made me listen to. I am sick of love/but I am in the thick of it. That was it – a kind of love-and-hate relationship with your lover, or mine. Inescapable. Maligned and loved, both in enormous proportions.’’

This is Sen writing in his late 70s, the quintessential Mrinal da, whom we haven’t really discovered in full. There are so many examples strewn in the book which illustrated the way he saw things – a particularly haunting one is his description of a young hapless father, holding the lifeless body of his child, waiting helplessly for cremation as the Nimtola burning ghat was witnessing a mob frenzy when Rabindranath Tagore’s body came there for cremation.

How was, by the way, his chemistry with Ray? A war of letters between the two, alongwith writer Ashis Burman, over the review of Akash Kusum obviously finds its way in the volume. Sen’s dig at Ray over the latter’s impressions on Bhuban Shome also doesn’t go unnoticed.

At the end of the day, you could have loved or hated Sen’s work, but could not ignore the influence he wielded on Indian cinema. A man who dared to break free of the conventions – and in a sense – was always being born!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!